The Hunt for the Perfect Clip

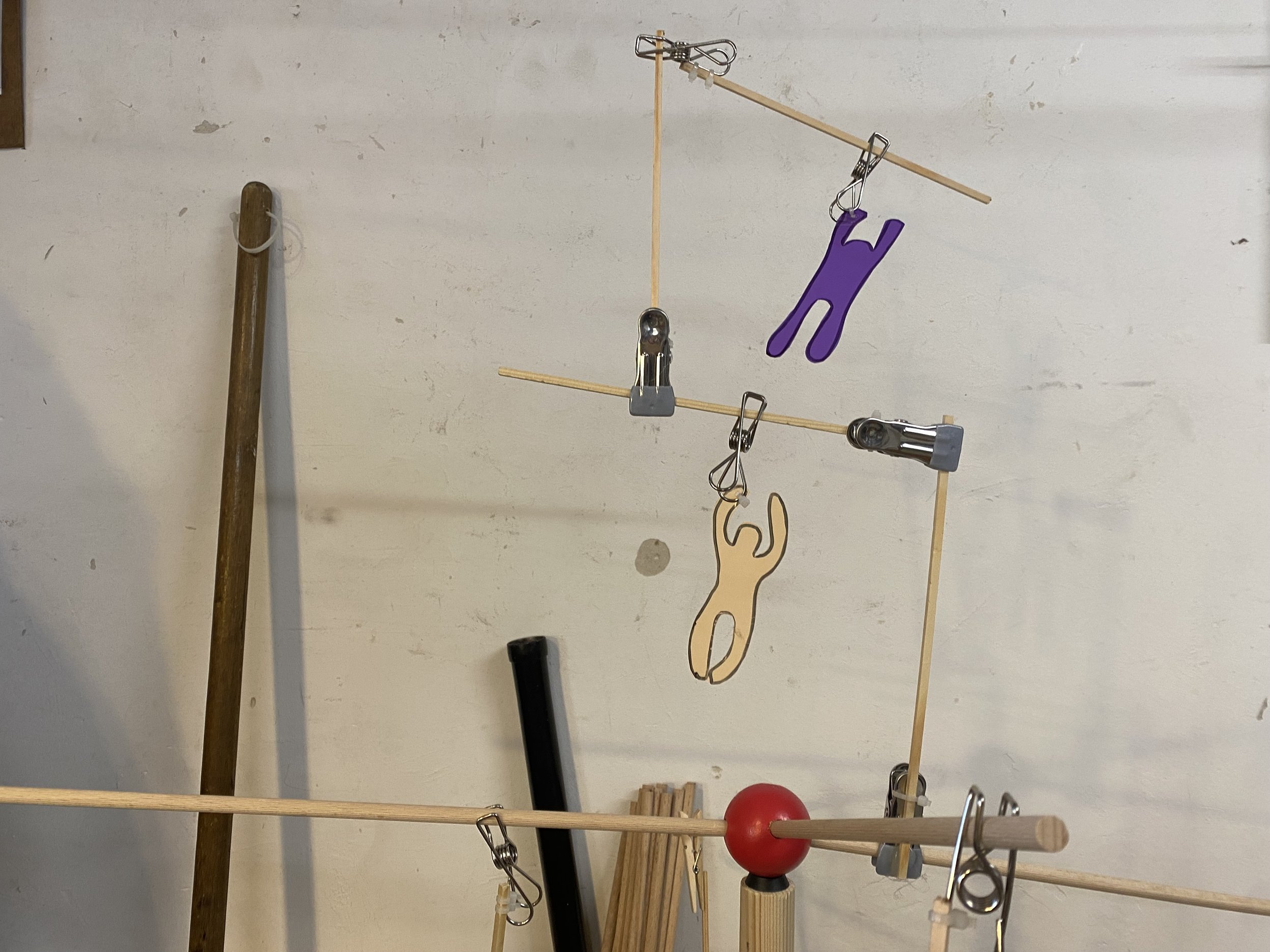

For the ‘ufte’ experiences that I’m developing alongside the team at the Exploratorium’s Tinkering Studio, there are many small elements that make a big difference in making the experience more engaging, intuitive and open-ended. For our balancing exploration we’re developing a system of clipping and sliding parts with clothespins because it allows learners to make small and delicate changes without disturbing the equilibrium of the system. We found the pushing pieces together and pulling them apart was too challenging in a way that took people out of the experience of investigating the phenomenon.

But once we arrived at the point where we knew we would use clips as a key component of the building process, there was still a lot of work to decide which type would work best to create a tinkerable experience. As a way to narrow the materials list, I collected a wide variety of clips including metal wire, flat metal, regular wooden clothespins, wooden clothespins with a larger spring, mini spring clamps and even a hi-tech locking clip. There were several qualities of the clips that I wanted to test out to help decide which ones to use for the activity.

For the clips, we are interested in a few qualities of the material. First is how easy they are to open, as we want this activity to be accessible to all ages. If the clips are too hard to press open, many younger children with smaller hands might get discouraged and not participate in the activity. Second is the strength of connection. We want people to have multiple ways to build balance sculptures that go high, way out to the side or down to the floor. If the clip is strong enough to hold onto the dowel without sliding, it won’t get in the way of them realizing their own designs. Third is reliability. We will be putting this activity on the floor of the museum for hours at a time without a facilitator. That means that the parts have to stand up to heavy use and can’t break too often. And the fourth quality that we are looking at is the aesthetics or design. We’d like to parts to fit together with the set, have a natural look that emphasizes the materiality and also have be recognizable so that people can realize that they are able to do something similar at home.

The classic wood clothespins that we might use for a normal tinkering activity were eliminated initially because we thought they would fall apart too easily. One interesting type that I found in my research had a larger spring so that the wood pieces can’t separate. These definitely are more stable but they weren’t as strong as some of the others that we tested. I would use them however for an activity like marble machines for an extended time on the museum floor over the normal clips.

There were issues with some of the other ones as well. The big red clip had a tiny connection point on the ends which made it hard to grip the dowel and the other metal and I felt that the red clip was too hard to open (even though it was really strong.

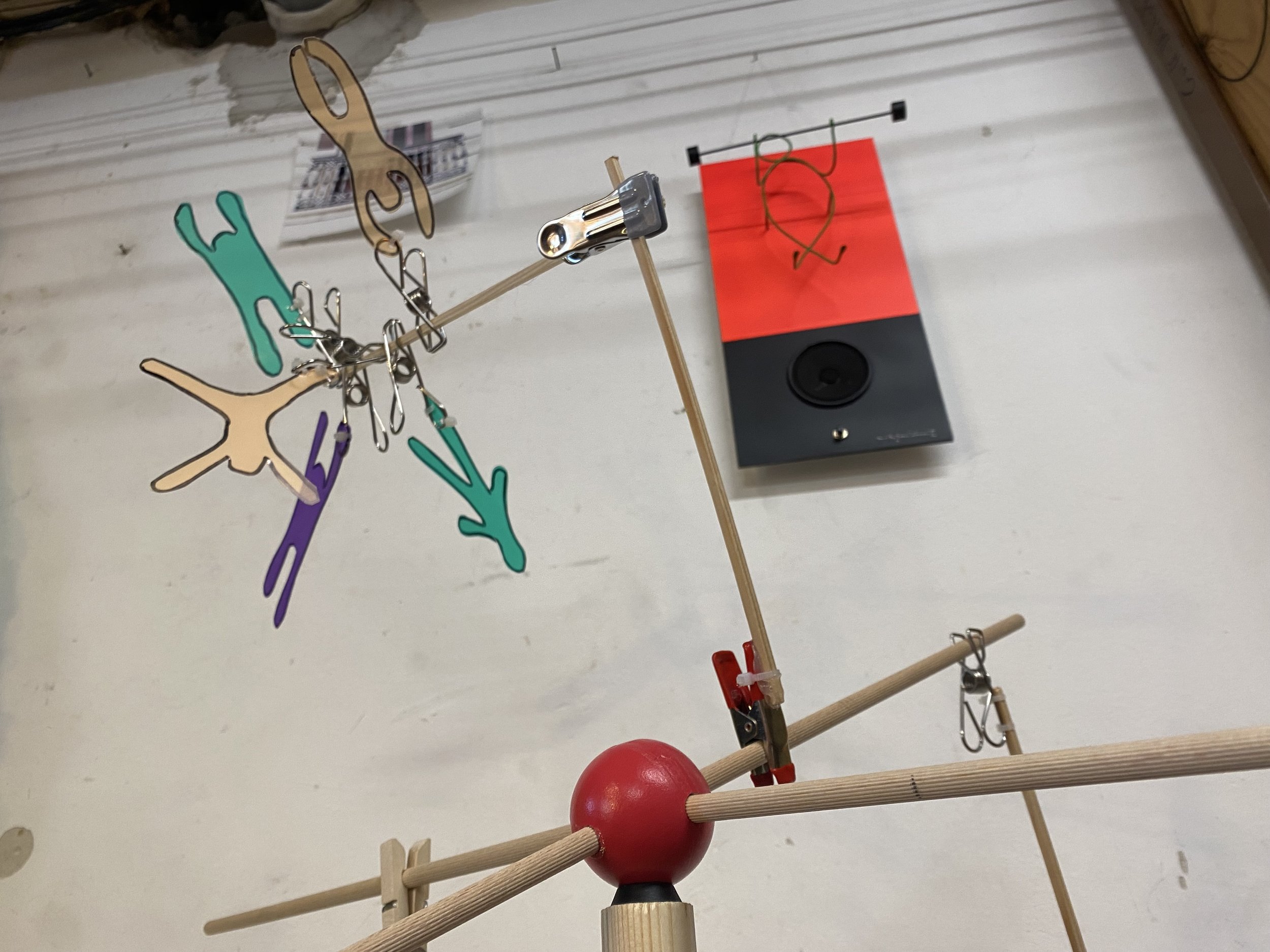

As a little test, I tried to see how many sticks and acrobats I could connect in a vertical line using the different sticks as the base before it started to fall over from the weight. The top three candidates in terms of strength were the red clip that was hard to open, the flat metal clip with the rubber grip and the metal wire.

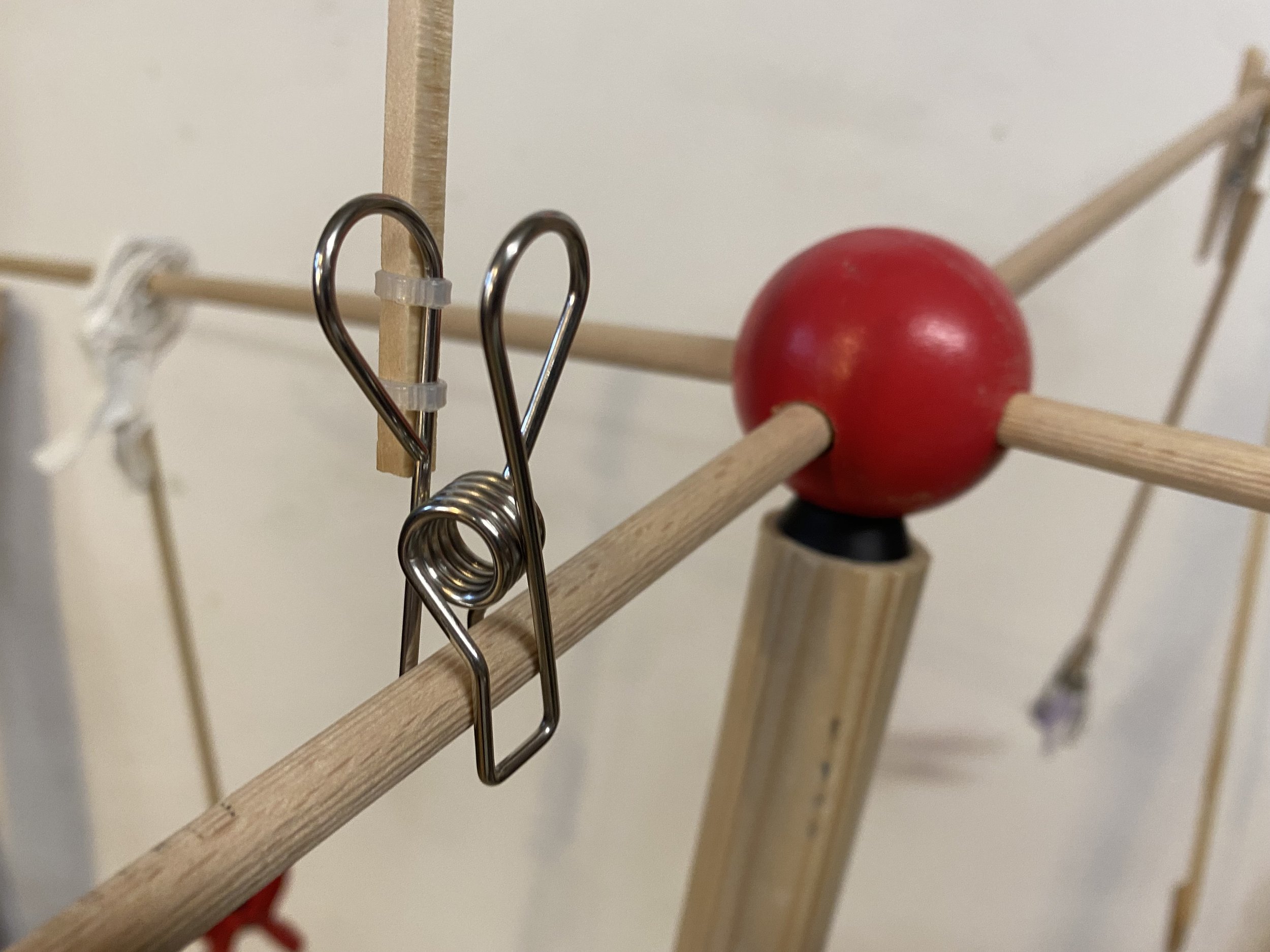

After all of the testing, I was most interested in trying out the flat metal rubberized clips and the metal wire ones. The wire ones felt a little easier to open but the flat ones were a bit stronger. The metal look of both of them seemed to be ok and I was confident that they wouldn’t break after use from visitors. They are a little less recognizable than the wooden clothespins but they don’t register as a custom hard-to-find part.

I used a combination of mini zip-ties, hot glue and heat shrink tubing to attach the clips to wooden sticks, translucent acrobatic figures and heavy weights for a couple of prototyping sessions last week. Each of these two clips were not that tricky to use to create the materials for our balance set.

From these tests I was really happy with the way that the materials support the building process. I could tell that learners were able to make many different designs without getting too frustrated by clips slipping. They were able to easily turn their ideas into physical prototypes using the parts to support the investigations.

There are so many little design choices for materials, prompts and environments that go into the development of tinkering activities. These small changes make it easier for participants to engage with the learning dimensions of intentionality, agency, social interaction and development of understanding. As well this is a really fun part of the R&D process. I hope that by sharing a behind the scenes look at just one of these stories, all of you educators and designers feel invited to join the process of supporting learners to tinker, play and explore.

The LEGO Playful Learning Museum Network initiative is made possible through generous support from the LEGO Group.